Transpose commonly used items from the dreariness of the quotidian into art.

Thus a coffee pot enters the Victoria and Albert Museum of London. And a corkscrew goes on show at MOMA (the Museum of Modern Art) in New York.

For Pino Spagnolo, architect and founder of Sigma Design in 1975 and later, in 1988, Pino Spagnolo Design (featured in Auto & Design Vol. 50), conducting his creations to such prestigious destinations does not signify the end of the journey, but the logical outcome of a way of  working. Of a world vision in which the prolific imagination of his homeland (Lecce, in the south of Italy) is mixed with the judicious reserve of what has become his adopted home town (Turin).

working. Of a world vision in which the prolific imagination of his homeland (Lecce, in the south of Italy) is mixed with the judicious reserve of what has become his adopted home town (Turin).

A specialist in household goods and domestic electric appliances, Pino Spagnolo Design works for the leading companies in these fields: Biesse (for whom he designed the corkscrew exhibited at MOMA), Simac, Philips, Krups, Siemens, Polti Vaporella, Bialetti Faema, McCulloch, Ariete, Meliconi, Saeco, GI.VI. and Pedrini.

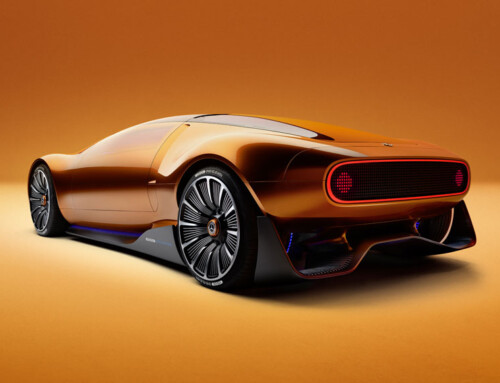

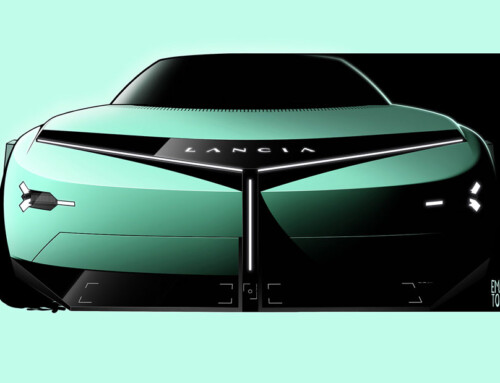

But there appear to be no limits to the eclecticism of Pino Spagnolo. Observe his Yamaha-framed bike proposals, electric cars and even trains. Pino Spagnolo Design has in fact produced a prototype train as part of a high-speed programme. And that’s not all.

For some time, he has also been successfully operating in the water-craft sector, with projects for the Alfamarine, Pietà, C.C.Y.D. and Gobbi Craft boatyards as well as for wealthy private customers, mostly from the Middle East and Japan.

From cutlery to electrical appliances, from bike boxes to saucepans, from boats to trains, without forgetting the interior architecture and building conversions. Does such variegation not risk transmuting into a dissipation of energy? “Not in the least,” says Pino Spagnolo, “because all our projects reflect a common company philosophy.

Today’s design is no longer associated simply with aesthetic and emotional factors. The designer is expected to have more and more specific technical skills, starting with the cost of materials, which inevitably affects the final price of the item.

“That’s why doing industrial design today means in the first place understanding and satisfying the precise needs of the company, but also seeking to equate with the desires of the end user. In this perspective, a coffee pot and a train have to have one basic characteristic in common: producbility. To this end, my colleagues and I, and they all have lengthy professional experience in my studio, always try to understand the production technologies of the commissioner before starting to design anything.”

The article continues in Auto & Design no. 108